by Aron Lund, editor of Syria in Crisis.

I wrote a post for Syria Comment last year listing the top events of 2014 and what to look for in 2015. So here’s another one—a very long one, in fact. It has been compiled in bits and pieces over a few weeks but was finalized only now, a few days after the fact.

In keeping with the buzzfeedification of international political writing, I have decided to make it a top ten list and to provide very few useful sources, just a lot of speculative opinion. I’ll rank them from bottom to top, starting with number ten and moving on to the biggest deal of them all. Enjoy!

10. The Death of Zahran Alloush.

In October 2013, the esteemed proprietor of Syria Comment, Professor Joshua Landis, compiled a top five list of Syria’s most important insurgent leaders, excluding al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and the Kurdish YPG. It contained the following five names:

In October 2013, the esteemed proprietor of Syria Comment, Professor Joshua Landis, compiled a top five list of Syria’s most important insurgent leaders, excluding al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and the Kurdish YPG. It contained the following five names:

- Hassane Abboud (Ahrar al-Sham)

- Zahran Alloush (Islam Army)

- Ahmed Eissa al-Sheikh (Suqour al-Sham)

- Abdelqader Saleh (Tawhid Brigade)

- Bashar al-Zoubi (Yarmouk Brigade)

Of these five, two remain alive but have been demoted to second-tier ranks in their factions. In March 2015, Ahmed Eissa al-Sheikh merged his group into Ahrar al-Sham and took up a less prestigious job in the new outfit. In October, the Free Syrian Army heavyweight Bashar al-Zoubi was reassigned to run the political office of the Yarmouk Army, as it is now called, and replaced as general commander by Abu Kinan al-Sharif.

The other three are dead. Abdelqader Saleh was hit by a missile in Aleppo in November 2013. Soon after, his powerful Tawhid Brigade began to fall apart. Most of its subunits are now dispersed across two rival-but-allied outfits, called the Levant Front and the First Corps, which are both active in Aleppo. Hassane Abboud was killed alongside other Ahrar al-Sham leaders in a September 2014 bombing—or whatever that was. And on Christmas Day 2015, Zahran Alloush suffered the same fate. A missile hit a building in the Eastern Ghouta where he was meeting with other local rebel leaders.

Since Zahran Alloush died just a week ago, we don’t know how much this will matter in the end. But he was indisputably one of the best-known rebel commanders in Syria, the one best positioned to dominate Damascus if Assad lost power, one of the very rare effective (because ruthless) centralizers within the Syrian opposition, a trusted ally of the Saudi government, and the most powerful Islamist leader willing to engage in UN-led peace talks. Those five qualities all seemed to promise him a major role in Syria’s future. But now he’s dead. And since his group always seemed like it had been built around him as a person, many now fear/hope that it will start unraveling like Saleh’s Tawhid Brigade in Aleppo. We’ll see. If the rebels start to lose their footing east of Damascus, it will be an enormous relief for Assad.

9. The Failure of the Southern Storm Offensive.

This summer, the loose coalition of rebel units known as the FSA’s Southern Front got ready to capitalize on a year of slow and steady progress, during which Sheikh Miskin and other towns had been captured from Assad. They encircled the provincial capital, Deraa, for a final offensive dubbed Southern Storm. The city actually looked ready to fall. After Idleb, Jisr al-Shughour, Ariha, Palmyra, and Sukhna, the fall of Deraa was intended to be the nail in Assad’s coffin and a show of strength for the Western-vetted FSA factions in the south, drawing support away from their Islamist rivals.

Stories differ on what happened next, but the Southern Storm campaign was a fiasco. Regime frontlines hardly budged, the Allahu Akbars trailed off into a confused mumble, and commanders were called back to Jordan. Half a year later, with Russian air support, Assad has begun an offensive to retake Sheikh Miskin in the hope of finally loosening the rebel stranglehold on Deraa—although at the time of writing, this is still a work in progress.

What happened? I really don’t know. Many things, probably. The operation seems to have been poorly coordinated, with rebels pursuing a plan that their foreign funder-managers in the Military Operations Center in Jordan didn’t agree on. Stories have been told about some nations cutting support, rebels defecting to Assad or heading for Europe, arms having been sold on to jihadis, and groups splitting over obscure internal intrigues. Some of those stories may be false, but the failure was a fact and the rebels have since been restrained from further advances.

Of course, it might seem strange to say that rebels not taking a city was Syria’s ninth most significant event in 2015. It is not even a Dog Bit Man story, it’s a Dog Didn’t Bite Man story. But the Deraa affair seems to have done a great deal of damage to Western and Arab hopes for the FSA’s Southern Front, which had until then been portrayed as a model for the rest of Syria’s insurgency. Unless the southern rebels manage to reorganize, unify, and go back on the offensive, I think the events of summer 2015 might end up being seen as a turning point in the southern war.

8. Operation Decisive Quagmire.

In keeping with local tradition, the princes of Saudi Arabia can be wedded to four regional crises at once. In early 2015, they were sulking over Syria, emotionally drained by Egypt, flustered by unfaithful Libya, and at wits’ end over that shrew in Baghdad, when Yemen suddenly walked into their lives—a huge, incoherent, boiling mess of splintering armed factions, collapsing institutions, Africa-level poverty, jihadi terrorism of every imaginable stripe, and aggressive interference by rival foreign governments.

In keeping with local tradition, the princes of Saudi Arabia can be wedded to four regional crises at once. In early 2015, they were sulking over Syria, emotionally drained by Egypt, flustered by unfaithful Libya, and at wits’ end over that shrew in Baghdad, when Yemen suddenly walked into their lives—a huge, incoherent, boiling mess of splintering armed factions, collapsing institutions, Africa-level poverty, jihadi terrorism of every imaginable stripe, and aggressive interference by rival foreign governments.

It was love at first sight.

Since then, the March 2015 Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen has of course turned out to be exactly the self-defeating, facepalm-inducing clusterfuck that everyone who is not a member of the Saudi royal family had predicted.

To make a long story short, the Saudis are still in Yemen with no victory on the horizon and no face-saving exit available. This means they have much less time and resources left for Syria than they did a year ago. They have become more exposed to Iranian pestering and are more dependent on their regional and Western allies, several of whom do not share their views on how to deal with Bashar al-Assad. Rather than being able to leverage their intervention in Yemen against Iran and Assad in Syria, the Saudis now seem at risk of having it leveraged against them.

Thanks to the over-confidence and under-competence of the Saudi royal family, Syrian rebels may therefore turn out to be among the biggest losers of the Yemeni war.

7. Europe’s Syria Fatigue vs. Assad’s Viability

The huge numbers of refugees coming from Syria and other countries to the European Union in 2015 had many causes, but one of the effects was to rearrange Europe’s list of priorities in the Middle East. Goals number one through three are now as follows: stability, stability, and stability. Number four is anti-terrorism, number five is economic growth, and then there are a few others along those lines. Promoting democracy is also on the list, right after ”fix the nose of the Sphinx.”

The huge numbers of refugees coming from Syria and other countries to the European Union in 2015 had many causes, but one of the effects was to rearrange Europe’s list of priorities in the Middle East. Goals number one through three are now as follows: stability, stability, and stability. Number four is anti-terrorism, number five is economic growth, and then there are a few others along those lines. Promoting democracy is also on the list, right after ”fix the nose of the Sphinx.”

In 2015, we have also seen a slow but persistent drip of terror scares and occasional massacres, including two big ones in Paris in January and November. This is obviously not the refugees’ fault, but many Europeans link these attacks to Syria anyway—including some of the attackers, like the wanker that began stabbing random people in the London Underground this December.

These things tap into the West’s darkest impulses. Reactions to immigration, painful social change, and terrorist pin-pricks may be irrational—in fact, they mostly are—but they carry real weight and win votes. Policy specialists might recommend some mixture of strategic patience, cautious reform, and nuanced rhetoric, but European rightwing populists eat policy specialists for breakfast.

Islamophobic far-right movements were already growing all over Europe, for reasons largely related to the continent’s own internal diseases, but the refugee crisis and the terror attacks are a godsend for them. Some of these groups are not content with merely hating and fearing the Syrian rebels for their Islamism, but also adopt pro-Assad positions. In addition, European extremists on both the far right and the far left are increasingly friendly with Putin’s Russia; some are even funded by the Kremlin. These parties are no longer bit players. They’re going to be in government soon, or close enough to government to shape policy. Add to that the old-school authoritarian national-conservatism that has begun to resurface in Eastern Europe, including Hungary, Poland, and other places, and the fact that countries like the Czech Republic and Hungary are already the Baath’s best advocates in the EU, and you have the nucleus of a slowly forming pro-Assad constituency.

Of course, many European politicians are also re-evaluating their views on Syria for perfectly non-racist and non-paranoid reasons. The most common one is probably a widespread and profound loss of faith in the Syrian opposition, not merely as an alternative to Assad, but even as a tool for pressuring him and engineering a solution. Others were never interested in a policy to overthrow Assad, although they happen to think he’s a crook.

The point is that all of these things now reinforce each other and for the Syrian regime, it looks like vindication. In 2011, Bashar al-Assad made a bet, wagering that (1) the West would one day recoil from its love affair with Middle Eastern revolution and return to the familiar comfort of secular authoritarianism, and that (2) his own regime would still be standing when that happened.

It is now happening, but whether or not Assad’s regime is still standing, qua regime, is a matter of definition. The Syrian president has so far shown little ability to exploit political openings like these. To an increasing number of European politicians, he does indeed look like the lesser evil, but also like a spectacularly incompetent evil. His regime appears to them to be too broken, too poor, too polarizing, too sectarian, too inflexible, and too unreliable to work with—more like a spent force than a least-bad-option. Assad’s diplomacy may be far more elegant but is ultimately no more constructive than that of Moammar al-Gaddafi, who, as you may recall, kept refusing every kind of compromise and even shied away from purely tactical concessions, until he was finally beaten to death by screaming Islamists in a country so broken it will perhaps never recover.

Then there is the question of Assad’s own longterm viability. Even in pre-2011 Syria, no one could be quite sure whether the Baathist regime would remain in one piece without an Assad at the helm. In a conflict like this, there must be dozens of assassins trying to worm their way into the Presidential Palace at any given moment and for all we know one of them could get lucky in 2016, 2017, or tomorrow. And what about his health? The Syrian president turned 50 this September. That’s no age for an Arab head of state and he looks perfectly fine in interviews. But if Western intelligence services have done their due diligence, they’ll know that his father Hafez suffered a ruinous stroke or heart attack at age 53, which nearly knocked him out of power. Who knows, maybe it runs in the family?

At this point, however, a growing number of European policymakers are so tired of Syria and its problems that they’ll happily roll the dice on Assad being the healthy, happy autocrat that he looks like. They would be quietly relieved to see Syria’s ruler reemerge in force to tamp down the jihadi menace and stem refugee flows with whatever methods, as long as they don’t have to shake his bloody hands in public and on the condition that he delivers a semi-functional rump state for them to work with, at some unspecified point in the future.

Obviously, Assad isn’t going to become best friends with the EU anytime soon, but it might be enough for him if major cracks start to appear in the West’s Syria policy. If so, there is now a window of opportunity opening up that wasn’t there for him a year ago. If the Syrian president manages to break some bad habits, tries his hand at real politics instead of Baathist sloganeering, and produces a stabilization plan slightly more sophisticated than murdering everyone who talks back to him, then 2016 could be the year that he starts breaking out of international isolation. If not, he’s likely to stay in the freeze box for at least another year—and since his regime keeps growing weaker, nastier, and less state-like by the day, it’s uncertain if he’ll get another chance.

This is a potential game changer worth watching, but don’t get too excited. Given the way that the Assad regime has conducted itself in the past half-century, the odds are long for transformative politics and persuasive diplomacy from Syria’s strongman.

6. The Vienna Meeting, the ISSG, and Geneva III.

While not the most important, the November 14 creation of the International Support Group for Syria (ISSG, not to be confused with ISIS or ISIL) was certainly the most unambiguously positive piece of news of the year.

While not the most important, the November 14 creation of the International Support Group for Syria (ISSG, not to be confused with ISIS or ISIL) was certainly the most unambiguously positive piece of news of the year.

A debating club of interested nations and international organs won’t be enough to end the Syrian war, but it means that the terms of the debate have been readjusted for the better. Recognizing the conflict’s international dimension and engaging constructively with the fact that this is now partly a proxy war was long overdue. As currently construed, the ISSG might be too broad and unwieldy to function properly, since the core players (USA, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, etc) always seem to have to hold preparatory pre-meetings before settling down in the ISSG format. But if that’s what it takes to get the screaming and sulking teenagers that rule Tehran, Ankara, and Riyadh to sit down and talk like adults, then so be it.

That the creation of the ISSG has for the first time made Iran a formal party to the Syria talks is a good thing, whatever Syrian rebels and their Saudi paymasters may think of it. Iran is a key player both on the ground and in the diplomatic struggle over Syria; that’s not something you can change by pretending otherwise, though many have tried. Of course, now we’re all waiting for Iran to come to the same conclusion about the Syrian rebels, instead of childishly insisting that Assad must be allowed to negotiate with an opposition of his own choosing.

After its meetings in Vienna and New York, the ISSG has empowered UN envoy Staffan de Mistura to call for a new round of Syrian-Syrian talks, currently scheduled for January 25 in Geneva. As many have already pointed out, these talks are unlikely to solve Syria’s problems. The ISSG-backed goal of a transition through free and fair elections by 2017 is almost cartoonishly unrealistic.

So, what to do about that? Many pundits have reacted to the Vienna statement and the Geneva peace process only by ridiculing it and then restating their preferences for the outcome. That’s not helping. The talks are indeed almost certain to fail to reach their overly ambitious goals, but then let’s work from that assumption instead of scoffing at it.

The actors involved in Syria’s war should plan for failure even more than they plan for success. They should already be preparing for a post-Geneva situation where they need to salvage, secure, and build on any shred of progress achieved in the talks.

Reaching a comprehensive ceasefire by June seems incredibly difficult, but a dampening of violence just might be possible, with some luck. If serious about it, Syrian negotiators could presumably also reach meaningful agreement on more limited and less controversial issues.

They could also agree to keep talking. Since so many now favor some sort of political resolution, and unsuccessful negotiations may give way to military escalation, it would be useful to avoid a full stop and the taste of failure. A faltering Geneva process could be drawn out into many sessions and postponed, with negotiators on both sides sent back for a couple of months to do their homework, instead of ended. Transforming the Geneva process into a semi-permanent platform for negotiations on a talk-while-you-fight model would transfer some of the combatants’ attention to a political track. That would be a good thing, both in the hope of achieving a breakthrough later on and for day-to-day crisis management.

Most of all, international actors should make sure to safeguard the ISSG framework, or some version of it, against an underwhelming performance in Geneva. Even if the war goes on and intensifies, some form of international contact group will be useful to facilitate communication and solve side-issues, and it remains a necessary ingredient in any future de-escalation deal.

5. The Donald.

The politics of the United States is a key part of the politics of Syria, although the reverse is rarely true.

The politics of the United States is a key part of the politics of Syria, although the reverse is rarely true.

Right now, it looks very likely that Donald Trump will either win the Republican nomination for president, or run as an independent and split the Republican vote out of pure spite. If so, Hillary Clinton is almost certain to be elected president of the United States, which would give her final say over the superpower’s Syria policy from January 2017 to 2020, or even 2024.

Of course, one never knows: some extraordinary scandal could knock her out of the race, or maybe Trump slinks away or is bought off after losing the primaries. We’ll see. But right now, Clinton seems like the smart person’s bet.

From what we know of her performance as President Obama’s secretary of state during the first three years of the Syrian war, a Clinton presidency would probably mean a more hawkish attitude to Assad. For example, she keeps declaring herself in favor of a no fly zone to ground the Syrian air force. Whether that is feasible is another matter, what with these Russian jets and air defense systems all over the place, and tough talk on the campaign trail will not necessarily translate into White House policy. But a more interventionist American line in Syria could definitely make a difference in the war, for good or bad or both.

The high likelihood of a Clinton presidency also means that we can tentatively exclude the sort of radical break in American Syria policy that might have followed a Republican restoration. Some of the GOP candidates are more aggressively anti-Assad than Clinton and have no interest in preserving any part of Obama’s legacy. Others are the exact opposite: more or less pro-Assad and starkly opposed to the rebels, whether for pandering to the anti-Muslim vote or out of anti-interventionist principle. But because of Donald Trump, it now seems like those points of view are going to get schlonged back into permanent opposition.

4. The Iran Deal.

The effects of the Iranian nuclear agreement, which was finalized between April and June 2015, are only very gradually becoming apparent. But unless the deal is somehow scuttled by the combined efforts of hawks in the United States, Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, it could reshape the region.

The effects of the Iranian nuclear agreement, which was finalized between April and June 2015, are only very gradually becoming apparent. But unless the deal is somehow scuttled by the combined efforts of hawks in the United States, Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, it could reshape the region.

As a consequence of the agreement and the American-Iranian thaw, the international isolation of Tehran is withering away. After four years of being shut out of Syria diplomacy, but not out of Syria, Iran has been invited to the UN-led negotiation process via the ISSG. The United States is also starting to accept Tehran as a regional power to be engaged coldly but constructively, although this is still unfamiliar terrain for all involved.

Meanwhile, European companies are flocking to Tehran to get a slice of the end-of-sanctions pie. Expecting billion-dollar construction contracts and racing to beat their Russian, Chinese, American, and Arab competition, the EU governments will soon start to pay a lot of attention to what Iranian diplomats have to say. More soft power for the ayatollahs, then.

Though often viewed, somewhat inexplicably, as a third-tier actor in the Iran talks, Russia is also paying the greatest attention to this process. Once the nuclear deal was done, Putin swiftly began to transform a complicated but friendly relationship into an emerging pact, seeing in Iran’s combination of oil, gas, military muscle, and poor ties to the West a perfect regional ally for Russia. Russian state media just announced that Moscow will start shipping its powerful S-300 air defense system to Iran next month.

This is all great news for Bashar al-Assad, of course, though it’s not yet clear whether his regime can stick around long enough to fully capitalize on Iran’s growing influence.

3. The Continuing Structural Decay of the Syrian Government.

Assad took some real body blows in spring and summer 2015. After an upward curve in 2014, the Syrian army started to seem exhausted by the end of the year and its offensive in Aleppo petered out after a last hurrah in spring 2015. With rising support for the rebels, the hollowed-out base of Assad’s regime began to show.

Assad took some real body blows in spring and summer 2015. After an upward curve in 2014, the Syrian army started to seem exhausted by the end of the year and its offensive in Aleppo petered out after a last hurrah in spring 2015. With rising support for the rebels, the hollowed-out base of Assad’s regime began to show.

Most obviously, Assad lost a lot of territory in the first half of 2015. In March, a coalition of Islamist rebels captured Idleb City in the north and Bosra in the south. In April, Jisr al-Shughour fell, followed by the Nassib border crossing to Jordan. In May, it was time for Ariha in Idleb, with other rebels pushing into the Ghab Plains. Further east, the Islamic State took Sokhna and Palmyra. Southern rebels grabbed a military base known as Brigade 52 in the Houran in June and began preparing their (ultimately ill-fated) assault on Deraa, the provincial capital. That same month, Assad’s forces in Hassakeh were mauled by the Islamic State. They survived only thanks to an uneasy alliance with the Kurds, which increasingly turned into dependence on them. In July, Assad was hard pressed and held a speech declaring that the army would have to focus on keeping the most strategic areas of Syria, though it would not stop striving for total victory.

The rebel and Islamic State offensives have mostly been blunted since then, thanks to raised levels of Russian and Iranian support, and they did not go far enough to deal critical damage to the regime. Yet, at the time of writing, Assad remains unable to recapture any of the cities he lost in the first half of 2015. The northern Hama front, in particular, continues to cause headaches for his government.

Even though you can’t see it on a map, Assad has also lost strength in other ways in 2015. His primary source of power—apart from the military—was always the fact that he controlled the state, and along with it a number of institutions on which every Syrian family relies, including courts, police, public services, state-run businesses and banks, and a system of food and fuel subsidies. While it does not mean that the regime’s subjects love their president, it has allowed Assad to co-opt, control, and mobilize millions of Syrians in ways that the insurgents cannot. Owning the government also allows Assad to hold out the promise of continued central control, institutional rollback in the provinces, and coordinated reconstruction—i.e., some sort of plan for a post-war Syria.

By contrast, his opponents may be skilled at breaking down existing institutions, but they have so far proven unable to build new ones that stretch further than a few towns. This weakness is a primary source of Assad’s strength.

The Islamic State and the Kurdish PKK are partial exceptions to the rule, clearly capable of organizing rudimentary governance after destroying, expelling, or subjugating regime-connected local elites. But, for various reasons, they are not credible alternatives to the existing central state. As for the situation in the remaining Sunni rebel regions, it is very bleak. After nearly five years, there is a handful of multi-province militias, three or so regional networks of Sharia courts (the Sharia Commission of Ahrar al-Sham & Co. and the Nusra Front’s Dar al-Qada in the north, and the more broadly based Dar al-Adl in the south), a lot of little local councils linked to the exile opposition, and a web of foreign-funded aid services operating out of Turkey and Jordan, but not much more.

When Idleb fell to the insurgency earlier this year, it was only the second provincial capital to slide out of Assad’s hands, after Raqqa. It was destined to become an example of what rebel rule would mean. And what happened? The city started out at a disadvantage because of the war, Assad’s retaliatory bombings, and so on. A decent number of public employees seems to have stayed and continued in their jobs, but salaries and electricity provision dried up. That meant that things like water pumps and schools went out of commission. Rebel factions did what they could to organize civilian life, such as forming a joint council, which has administered the city through some combination of inherited municipal regulations and Sharia law. Despite the prominent role of al-Qaeda in the Jaish al-Fath coalition now running Idleb, foreign governments have chipped in by donating food and medical supplies to avoid a humanitarian disaster. Still, even under a comparatively well-organized, broadly based, and locally rooted coalition like Jaish al-Fath, the basics of a new political order never seem to fall in place. After eight months of insecurity, crime, and armed men swarming the city, the new rulers have yet to organize a credible police force. Whatever the opposition may claim, such failures are not merely the result of Assad’s barrel bombing.

The rebels’ manifest inability to govern, along with merciless airstrikes on nonregime territory, is what makes Assad able to compel most of the population to live under his rule; and the fear of irreversible state collapse is what has made foreign states hold back support from the rebels at critical junctures. However, this key advantage of the Assad regime is also slowly fading away, along with the state itself. The resulting problems are almost too many to list.

For one thing, the Syrian army’s manpower deficit is turning into a major issue. Assad has mobilized his security apparatus to hunt down draft dodgers through house calls and flying checkpoints, in order to replenish thinning ranks. The main effect seems to have been to send a growing stream of seventeen and eighteen year old men across the border, often with their families in tow. They may or may not prefer the government over the rebels, it doesn’t matter. In a Syria at peace they would have grumblingly gone for their one-and-a-half years of army training. But as things stand, they know full well that army service has no time limit: discharge is equal to death. As it turns out, most Syrians have no intention of giving their lives in service of Bashar al-Assad and draft dodging is now pervasive. Tensions have become so great that in the Druze-majority Sweida region in the south, the government apparently decided in 2015 to abstain from normal recruitment to the Syrian Arab Army out of fear of provoking a local rebellion. Druze men can instead report for home defense units, on the understanding that they won’t be shipped away to die in distant Hassakeh or Latakia. A similar arrangement reportedly applies in Aleppo and they seem to be creeping into other regions as well.

On the frontlines, Shia foreign fighters are taking a greater role. They appear to be behind much of the successful offensive south of Aleppo. Iran is rallying Iraqi and Lebanese fighters with both religious and financial inducements, but its client groups—Hezbollah, the Badr Organization, Asaeb al-Haqq etc—do not seem able to mobilize enough fighters. According to some reports, Iranian authorities have resorted to press-ganging young Hazara Shia refugees into going to Syria, under threat of deporting their families back to Afghanistan.

Russia has acted even more decisively, by sending its own air force and huge amounts of military materiel to shore Assad up.

Drawing on all of these resources, the Syrian president and his allies have managed to supply the army with the manpower it needed to regain some sort of strategic composure after the difficult first half of 2015. The army now seems to stand its ground again. But though the regime’s counterinsurgency apparatus is now back in working order, this is still the military-logistical equivalent of fixing your car engine with chewing gum and a prayer.

Though it remains the country’s single most powerful armed force, the Syrian Arab Army appears to have boiled down to a skeletal organization. Many elite and specialist units remain in service, but officers have far fewer regular soldiers under their command and are haphazardly recruiting local hangers-on to pad out the ranks in their sector. A huge number of more or less local militias have been set up by pro-Assad civil society figures, including businessmen, neighborhood strongmen, and tribal leaders, and Iran has helped Assad to organize tens of thousands of fighters under the National Defense Forces umbrella. Much of the broader ground force has thus been replaced by local irregulars, although army and intelligence officers still appear to oversee the action and report back to Damascus.

An example of what the Syrian Arab Army now looks like is Brigade General Soheil al-Hassan’s Tiger Force. So called after its commander, whose nickname is ”The Tiger,” it is one of the government’s most acclaimed elite units, which shuttles back and forth across northern Syria to put out fires and break up stalemates. While the Tiger Force is presented in regime media as an exemplary representative of the regular Syrian Arab Army, Hassan is in fact an air force officer who reportedly served as part of Air Force Intelligence at the Hama Airport when the conflict began. Having moved into a frontline role from 2011 onwards, he does not seem to control a huge force, instead relying on local troops and a smaller entourage of personal loyalists from varied backgrounds. Even now, when he is stationed on the front against the Islamic State east of Aleppo, he is surrounded by some of the local militias he worked with in Hama earlier in the war.

The civilian side of the government is also suffering. The state economy has declined at an accelerated pace since summer 2014. Then, the Syrian pound began to lose value quicker, fuel supplies dwindled, and the government was forced to begin a painful retreat from its costly system of subsidies for basic goods. Assad also lost access to the Jordanian border in 2015, complicating trade with Iran and the Gulf Arab markets and hurting farmers and other exporters. Iran’s decision to turn the credit tap back on in spring 2015 surely helped to slow the decay. But with Assad having run down his currency reserves and facing an array of other problems, the value of the pound continues to melt away, the lack of fuel causes cascading problems throughout the economy, the institutional rot worsens, and we’re seeing an accelerating middle class exodus from Damascus and the big cities.

When I recently polled some specialists on the Syrian economy, answers were uniformly pessimistic. Jihad Yazigi, who publishes the well-regarded economic newsletter The Syria Report, concluded that 2016 will see Syrians ”poorer, living a more miserable life, and emigrating in higher numbers.” José Ciro Martínez, an expert on food in conflicts, noted that bread prices have tripled in government-controlled areas (and also in the parts of Syria under Islamic State control), while they are stabilizing in rebel-held regions, where foreign governments are trucking in flour and food.

For the Baathist government, which still today controls a sizable majority of the Syrian people, this has started to eat away at one of Assad’s most important competitive advantages: his ability to provide basic goods and salaries in areas under his control, which draws civilians away from the bombed out and broken rebel badlands and places them under the control of his state, army, and security apparatus. In the past year, humanitarian workers and diplomats monitoring these issues have started to speak about internally displaced people being turned away from government areas that no longer feel that they can afford to care for them, or view them as potential fifth-columnists for the Sunni insurgency. The situation is so bad that in northern Syria, thousands have headed for Islamic State-run Raqqa—a city ruled by fundamentalist psychopaths and targeted by a dozen different air forces, but still safer and more livable than wherever they came from.

The decay of the central government, the army, state institutions, and the Syrian economy more generally means that Assad is growing less credible as the steward of all or part of post-war Syria, even for those inclined to imagine him as such. For years, the Syrian government has spent considerable resources running basic governmental functions even in areas outside of its control—for example by paying salaries to government workers, teachers, and hospital staff in some opposition-held regions. As a consequence, many insurgent areas are paradoxically enough dependent on regular payments and institutional services from the government they’re fighting.

In some cases, these are quid pro quo deals, where the government tries to leverage its ability to shut down services, in order to get the rebels to let traffic through a checkpoint or stay out of certain towns. In other cases, there are overriding shared interests, such as when the government and Islamists work out arrangements to keep Damascus and Aleppo supplied with potable water. There is also the spectacle of unhappy government oil workers sent out to run power plants under Islamic State supervision, because both sides want to keep the lights on and hope to make money off of the other.

But in many other cases, the central government simply seems to be paying for services in areas it does not control. This is not a humanitarian measure and neither is it mere bureaucratic inertia. (Sometimes, the government shuts down services and stops food deliveries as a means of collective punishment.) Rather, it appears to result from a strategic choice to maintain a skeletal grid of institutions in as many regions as possible. That’s a core interest for the Syrian state as such, but also for Assad personally, who hopes to win the war by safeguarding the government’s institutional base and making it contingent on the continued existence of his regime.

Given current trends, it seems unlikely that the central government will be able to keep these payments up forever. In so far as the current rulers of the state are forced to chose, they will no doubt prioritize loyalist areas. (Or corruption and clientelism will make that choice for them.) Also, many areas have already lost any presence of the state and functioning public institutions, whether due to the war, rebel depravations, or regime terror bombing. Recreating them will be even more costly than just keeping them in operation. If Assad’s government does not have the resources or the institutional capacity to rebuild reconquered areas, then it will rule no more effectively than the rebels. If it turns out to be too dependent on radical sectarians to allow Sunni refugees back, and cannot in fact operate as an institutional state and a national government, then President Assad is just a warlord with a fancy title.

For the regime, this is a do or die issue. Unless it manages to bring these structural problems under control in 2016, Syria may be heading into unknown territory.

2. The American-Kurdish Alliance.

Since late 2014 and early 2015, the United States Air Force has transformed itself into something that more closely resembles the Western Kurdistan Air Force. Under U.S. air cover, Kurdish forces are constructing their own autonomous region (called Rojava) and in autumn this year, the U.S. started delivering ammunition and small arms directly to Arab units working under the Kurdish umbrella, currently called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). We’re still in the early stages of what may or may not turn out to be a longterm relationship, although certainly not a monogamous one.

Since late 2014 and early 2015, the United States Air Force has transformed itself into something that more closely resembles the Western Kurdistan Air Force. Under U.S. air cover, Kurdish forces are constructing their own autonomous region (called Rojava) and in autumn this year, the U.S. started delivering ammunition and small arms directly to Arab units working under the Kurdish umbrella, currently called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). We’re still in the early stages of what may or may not turn out to be a longterm relationship, although certainly not a monogamous one.

Militarily, it is a match made in heaven and the results are impressive. Despite their limited numbers, the Kurds have created a disciplined force that uses air support effectively. They’re chewing up jihadis and spitting them out from Kobane to Hassakeh. At the moment, they’re threatening to march against Shedadi near the Iraqi border and have just seized the October Dam on the Euphrates, giving them land access to Manbij and the Aleppo hinterland.

Such victories do not look like much on the map, but they are doing systematic and significant damage to the jihadis in sensitive areas. Oil fields, roads, border crossings, and bridges: these are things the Islamic State cannot live without. Now, the American-Kurdish coalition is buzzing around northern Syria like a giant vacuum cleaner, gobbling up all those goodies and leaving nothing for anyone else. If 2016 turns out to be the year when the Islamic State begins to crack and contract, the Syrian Kurds will have played a huge role in getting us there.

Politically speaking, however, the American-Kurdish alliance is not such a perfect marriage. It’s more like an unfortunate Tinder date: initial ambitions align, but you don’t have a lot of interests in common and your friends roll their eyes.

First of all, the Kurds are an ethnic minority with a very particular set of problems and ambitions in Syria, which have little to do with the wider war within the Sunni Arab majority. Their current crop of leaders are ideologically doctrinaire PKK loyalists. They have atrociously poor relations to the rest of the U.S.-backed opposition and disturbingly (as seen from the White House) close contacts with Moscow. If it wishes to act on the central stage of Syrian politics, the United States ultimately needs to win strong allies within the religiously flavored Sunni Arab majority, but it has instead come to rely on a foreign-linked, Russian-friendly, authoritarian, and secular Kurdish group with a (partly undeserved) reputation for separatism. Needless to say, this rubs every dominant ideological camp within the popular majority the wrong way: Islamists, Baathists, Syrian nationalists.

Secondly, the PKK is listed as a foreign terrorist organization in the United States. That means it is illegal for American citizens to provide it with any form of ”material support or resources,” possibly including enormous truckloads of ammunition and billions of dollars worth of close air support. Of course, the sanctioning of the PKK is more due to its violent conflict with Turkey than because of any Kurdish attacks against Americans. Therefore, one would logically expect there to be at least a debate in the United States about whether this key anti-jihadi ally should perhaps be removed from the black list, since this would seem to be an urgent national security interest. But there is nothing of the kind. Instead, the executive branch just goes about its business and the PKK gets its guns as intended. It is a rare case of a political system being so dysfunctional that it becomes super-functional, but it might not last forever.

Third and last, but not least—you may have heard of NATO. The United States is in a military alliance with Turkey, which is a key backer of the Syrian Sunni Arab opposition but also the PKK’s arch-enemy. Both Ankara and the Kurds rank each other far higher than Assad or the Islamic State on their respective lists of evils for urgent destruction. It’s getting worse, too. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is currently sending jets and tanks to bomb Kurdish cities, and he is backing attempts to destroy the HDP, which serves as PKK’s Sinn Féin and is a necessary component of any peaceful solution to Turkey’s conflict. If Turkey-PKK relations were antagonistic before, they are positively murderous right now.

These contradictions threaten to rip apart the United States’ Syrian alliance network, undermining its policy to pressure both Assad and the Islamic State. Resolving them is probably impossible; ignoring or transcending them won’t be much easier. At the moment, the United States is drifting towards the PKK almost by default. This is both because the Kurds have offered something that actually works on the ground and because Erdogan has been such a singularly unhelpful ally in Syria. Turkish obstructionism may have started to fade away now, with Ankara belatedly realizing its need for Western support and the costs of playing spoiler. That could change things. But unless Turkey’s behavior changes radically and other current trends continue, the unlikely alliance between the Pentagon and the PKK looks like it might just beat the odds and survive for the long term.

1. The Russian Intervention.

Here we are, at number one, and it’s an easy choice. The single most important event of the Syrian war in 2015 was of course Russia’s September 30 military intervention. Unfortunately, it’s much harder to pin down exactly why this is so important: because it strengthened Assad so much or because it didn’t strengthen him enough?

Here we are, at number one, and it’s an easy choice. The single most important event of the Syrian war in 2015 was of course Russia’s September 30 military intervention. Unfortunately, it’s much harder to pin down exactly why this is so important: because it strengthened Assad so much or because it didn’t strengthen him enough?

Most of the discussion in Western Europe and the United States has been over whether Russia intervened against the Islamic State, as it claims, or against other rebels backed by the United States, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. That question is easy to answer: Russia did not intervene against anyone in particular, it intervened for Assad. Who gets hurt depends on who stands in his way. So far, attacks overwhelmingly focus on the other rebels, not the Islamic State—although the Russian government and its media toadies continue to claim otherwise with a sanctimonious pigheadedness unseen since Baghdad Bob.

If we instead judge the Russian intervention against its undeclared but actual goal, which is to aid Assad, a nuanced picture emerges. The airstrikes themselves are intense and seem effective, but they will ultimately matter little unless a capable ground force can exploit the openings created. Assad’s army leaves much to be desired, as already noted, and his government will struggle to resume firm control over the areas and populations it might capture.

So far, there have been limited gains on the ground, mostly in low-value areas south of Aleppo and some hard-won mountain terrain in northern Latakia. The Syrian army is also seeking to wrest back control of Sheikh Miskin in the south, to make Deraa easier to hold. Less visibly but perhaps more importantly, a series of local ceasefire-and-evacuation deals have helped neutralize rebel strongholds in the Homs and Damascus regions. Since the costs to Russia seem to be fairly limited, they can probably keep this up for a long time, meaning that Assad is in no hurry and can focus on preserving cohesion and manpower.

But on the other hand, three months have already passed and Assad has not recaptured a single one of the cities he lost in spring and summer 2015. Not Jisr al-Shughour, not Bosra, not Idleb, not Palmyra. And on the North Hama front, which has been a main focus for the Russian Air Force, Assad has actually been pushed backwards. Soon after the Russians intervened, he lost Morek, a small town that has been fiercely contested for both sides; that was no sign of strength. If the rebels were to move just a few villages further south of Morek, they’d be within comfortable range of Hama City and could start shelling the crucially important Hama Military Airport. (Perhaps that is a reason for why Assad and the Russians are now hastily restoring the discontinued Shaayrat Airport southeast of Homs?)

In other words, while the intervention has helped Assad turn the tide, he’s nowhere near as effective at capturing territory as his enemies were half a year ago. By now, the initial shock and awe has started to wear off. The Russian state media continues to claim that they’re winning, winning, winning, but if people were willing to listen to that on September 30, they don’t any longer. After three months of nonstop lying and braggadocio, the progress reports from Russia’s ministries of defense and foreign affairs seem no more credible than the shrill propaganda we’ve grown accustomed to from Syria’s rebels and regime.

That said, I think it is quite possible that the Russian bombings will have made a deep cut in the rebellion’s fortunes by spring 2016. The longterm and cumulative effect of all this pressure should not be ignored. How long can the Idleb insurgents fight a three-front war against forces coming from Aleppo in the east, Latakia in the west, and Hama in the south? Both the Syrian and the Russian air forces are now hitting munitions storages, supply routes, and transports all over Idleb and Aleppo. The longer-term effects of these bombings may remain invisible to us still. They are also bombing civilian trade and points of access for food and medical aid in areas that had previously been off limits to the Syrian air force. This is either a calculated gamble or part of a deliberate strategy to create a humanitarian disaster, since the Russians are well aware that hundreds of thousands of people depend on deliveries channeled through these areas. Whatever the case, it stirs up the situation all over northern Syria. Rebel forces could theoretically begin to unravel structurally in the same way that the Islamic State is now doing on some fronts, after a year of mostly Iraqi, Kurdish, and American pressure.

Indeed, we are seeing signs that all is not well in the Syrian rebel movement. The Jaish al-Fath coalition, a powerful Idlebi alliance built on the Nusra-Ahrar axis, has just issued a desperate-sounding call for outside support and foreign fighters. The fact that the alliance now openly invites foreign jihadis to come join them breaches a longstanding redline for the non-Qaida segments of the Islamist opposition. One of Jaish al-Fath’s founding factions, the Muslim Brotherhood-aligned Feilaq al-Sham militia, was so troubled by this (and perhaps by how their funders would react) that they pulled out of the alliance days after the statement. That Jaish al-Fath’s dominant factions would throw caution to the wind in this way, to the extent that the alliance is starting to wither, is a sign of how much pressure they are under since September 30.

Another possible metric is the death of senior commanders. There is no shortage of new recruits for the rebellion, so one shouldn’t overstate the overall significance, but if leaders get killed it’s at the very least a sign that something is wrong. Since September 30, there has been a lot of reports about dead and injured senior figures in the insurgency. The most well known victim is of course Zahran Alloush in Damascus, though we do not know if the Russians were involved in that attack. Further north, recent deaths include Abu Abdessalam al-Shami, an Ahrar al-Sham member who served as Jaish al-Fath’s governor of Idleb City, Ismail Nassif, who was the military chief of the Noureddine Zengi Brigades, and his counterpart in the Thuwwar al-Sham Front, Yasser Abu Said. All three were killed on the south Aleppo front. Jaish al-Fath’s chief judge, the Saudi celebrity jihadi Abdullah al-Moheisini, was wounded just before Christmas (but survived), while Sheikh Osama al-Yatim, who ran the Dar al-Adl court system in the Houran, was killed in mid-December. The list could be made a lot longer.

It’s also worth noting that the political effect outside Syria has been far bigger than the military gains inside Syria. September 30 shook up conventional wisdom about the conflict and increased Putin’s influence across the board, for having yet again out-escalated the West and proven his commitment to Assad. It created some hard-to-win debates for John Kerry, added to an already growing European pessimism about the wisdom of backing Syrian rebels, and made it less likely that a no fly zone would be imposed in Syria by Obama or his successor. By focusing the minds of people in Moscow, Washington, and elsewhere, the Russian intervention has also helped bring about the Vienna meetings, the creation of the ISSG, and consequently also the upcoming Geneva III talks in January. The November 14 Vienna Communiqué (which Assad doesn’t like) is now overtaking the Geneva Communiqué of June 2012 (which Assad really hated). However you rate these things, they’re not nothing.

Most analysis of the Russian involvement has been so politicized as to be almost useless. Putin’s and Assad’s supporters have been quick to pronounce the operation a resounding success, while rebel backers dismiss it as a murderous fiasco. The safe bet is, as always, to look for the truth somewhere in between those extremes. My best guess is that Putin is probably worried over the Syrian Arab Army’s underwhelming achievements and increasingly concerned over what he has gotten himself into. Nevertheless, Assad is definitely in a stronger position than he was half a year ago and can still hope for a bigger dividend in 2016. One also has to consider the alternatives: the Syrian army would no doubt have been much worse off now if the intervention had not happened, and that would have undercut Russia’s influence as well.

Finally, one must note the risks involved in raising the stakes. If the Geneva III talks falter and Assad fails to achieve a decisive breakthrough in 2016, then what? Russia can hardly pull back, now that Assad has grown dependent on its support, not without losing face and seeing its investments frittered away. And what then, Mr. Putin: will you just keep going with no end in sight, or will you escalate even further? In other words, Russia is now at risk of getting stuck in an intractable conflict without an exit strategy and without clear political gain. It would be like Saudi Arabia in Yemen, but on a much bigger scale. If Putin ends up sending ground troops into battle, the risks and costs involved would rise considerably—but even that might not be enough to bring about a Kremlin-friendly conclusion to the Syrian mess.

Some of the less responsible actors on the pro-rebel side (you know who you are) might find this scenario to be in their interest. By exposing himself to injury in Syria while simultaneously continuing to provoke Western and Sunni Arab nations in Ukraine, Iran, and elsewhere, Putin has effectively offered them the choice of a full-blown proxy war. Once he seems to have tied his personal prestige firmly enough to Assad’s fate, they just need to abandon any lingering hopes they might have for stability in Syria and start kicking at the pillars that still keep the state standing, thereby turning Syria into Putin’s own Afghanistan. It would be very bad news for the Russians, but it would be a catastrophe for Syrians.

Barring a military breakthrough, much could depend on the outcome of the otherwise uninspiring Geneva III talks in January. The behavior of Russia and the Assad government will be watched closely by Western states. If Putin acts constructively and demonstrates real leverage over his ally, or meaningful agreements between Syrians seem to be within reach, then so far so good. But if it turns out that Putin refuses to fulfill his side of the deal, which is to deliver Assad’s approval of a transition plan, or if Assad simply ignores Moscow’s advice, then what good is the Russian presence in Syria to Arabs, Americans, and Europeans? We would be back in a purely military contest. The ramped-up Russian investment in Assad’s regime would then look less like a unilateral readjustment of Syria’s balance of power and more like a target of opportunity.

The post The Ten Most Important Developments in Syria in 2015 appeared first on Syria Comment.

President al-Assad’s First Speech – An Insider’s Account

President al-Assad’s First Speech – An Insider’s Account

India and the Syrian Conflict

India and the Syrian Conflict

The Sunni extremist group known as Islamic State (IS, also known by an earlier acronym, ISIS) is taking a terrible beating. In the past few days, it has lost territory in both Syria and Iraq. Syrian Kurds have attacked it east of Aleppo and north of Raqqa City, while it is battling Sunni Arab rivals north of Aleppo. The Syrian army of President Bashar al-Assad is pressing into the Raqqa Governorate and taking ground in the deserts east of Palmyra. In Iraq, other Kurdish groups have struck east of Mosul, while an alliance of Shia militias and the Iraqi army is moving into its stronghold in Fallujah. Further afield, the jihadis are being purged from the Libyan city of Sirte.

The Sunni extremist group known as Islamic State (IS, also known by an earlier acronym, ISIS) is taking a terrible beating. In the past few days, it has lost territory in both Syria and Iraq. Syrian Kurds have attacked it east of Aleppo and north of Raqqa City, while it is battling Sunni Arab rivals north of Aleppo. The Syrian army of President Bashar al-Assad is pressing into the Raqqa Governorate and taking ground in the deserts east of Palmyra. In Iraq, other Kurdish groups have struck east of Mosul, while an alliance of Shia militias and the Iraqi army is moving into its stronghold in Fallujah. Further afield, the jihadis are being purged from the Libyan city of Sirte. By Joshua Landis – Director, Center for Middle East Studies, Univsity of Oklahoma

By Joshua Landis – Director, Center for Middle East Studies, Univsity of Oklahoma Nicholas A. Heras

Nicholas A. Heras Assad Hopes to Make Aleppo a Turning Point in the War

Assad Hopes to Make Aleppo a Turning Point in the War By Ammar Abdulhamid – He was a fellow at Brookings and the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. He was the first Syrian to testify to congress against what he viewed as crimes by the Syrian president.

By Ammar Abdulhamid – He was a fellow at Brookings and the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. He was the first Syrian to testify to congress against what he viewed as crimes by the Syrian president.

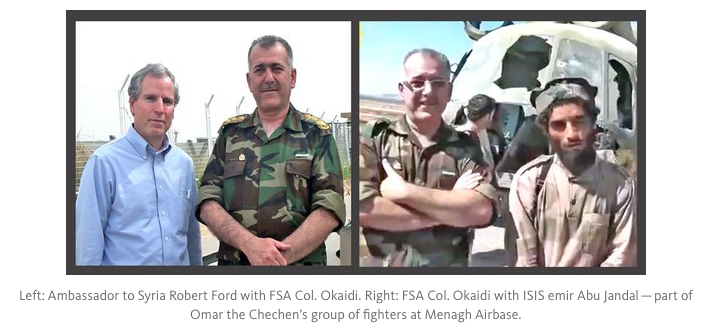

The Syrian coalition and military commanders, such as Colonel Abdul Jabaar al-Aqidi, were the principal allies of the west. Pictures of the Colonel standing with foreign jihadists who belonged to the Islamic State during the capture of Kuweiris air base and subsequently standing with Ambassador Robert Ford became iconic of Washington’s confused strategy in Syria. Many accused Washington of indirectly supporting the same jihadists that it sought to destroy. This doomed policy was a result of conflicting goals. The West and its regional allies wanted stability and regime-change at the same time. They wanted to support a Sunni ascendancy in Syria without undermining secularism. On the ground, however, the extreme right side of the opposition spectrum kept moving left and swallowing all others in its path. To date, the main elements of the opposition blame President Obama for the Syrian crisis. They propose a variety of policy alternatives, such as bombing Damascus, destroying the Syrian air force, establishing no-fly-zones, and increasing money, arms, and training for the opposition. These critics are now placing their bets on Hillary Clinton, who promises to be more hawkish than Obama. They hope that she will tilt U.S. foreign policy more decisively in the direction of regime-change. Her campaign advisors suggest that Hillary may indeed move in this direction. But any escalation by Washington is only likely to produce an even stronger escalation by Moscow. Hillary’s campaign promises are likely to be moderated once she is president.

The Syrian coalition and military commanders, such as Colonel Abdul Jabaar al-Aqidi, were the principal allies of the west. Pictures of the Colonel standing with foreign jihadists who belonged to the Islamic State during the capture of Kuweiris air base and subsequently standing with Ambassador Robert Ford became iconic of Washington’s confused strategy in Syria. Many accused Washington of indirectly supporting the same jihadists that it sought to destroy. This doomed policy was a result of conflicting goals. The West and its regional allies wanted stability and regime-change at the same time. They wanted to support a Sunni ascendancy in Syria without undermining secularism. On the ground, however, the extreme right side of the opposition spectrum kept moving left and swallowing all others in its path. To date, the main elements of the opposition blame President Obama for the Syrian crisis. They propose a variety of policy alternatives, such as bombing Damascus, destroying the Syrian air force, establishing no-fly-zones, and increasing money, arms, and training for the opposition. These critics are now placing their bets on Hillary Clinton, who promises to be more hawkish than Obama. They hope that she will tilt U.S. foreign policy more decisively in the direction of regime-change. Her campaign advisors suggest that Hillary may indeed move in this direction. But any escalation by Washington is only likely to produce an even stronger escalation by Moscow. Hillary’s campaign promises are likely to be moderated once she is president.

The identity crisis promoted by Saudi Arabia in Syria as well as its anti-Shia and anti-everything rhetoric has contributed to Washington and Tel-Aviv’s struggle against the “Axis of Resistance.” By depicting the countries and movements opposed to Israel as a “Shia Crescent” and as a threat to the Sunni world, Washington and Riyadh have succeeded in diverting the focus from the Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights and in the West Bank, to Iran, Syria and Hezbollah. The misguided and perilous instrumentalization of jihadist organizations is reminiscent of the role assigned to Osama Bin Laden’s Mujahideen in Afghanistan in the 1980s. But this time, the US-backed Saudi, Qatari and Turkish strategies in Syria might prove to be exponentially more disastrous. In the wake of this foolish adventure, religious minorities have nearly disappeared in the so-called “liberated areas” in Syria.

The identity crisis promoted by Saudi Arabia in Syria as well as its anti-Shia and anti-everything rhetoric has contributed to Washington and Tel-Aviv’s struggle against the “Axis of Resistance.” By depicting the countries and movements opposed to Israel as a “Shia Crescent” and as a threat to the Sunni world, Washington and Riyadh have succeeded in diverting the focus from the Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights and in the West Bank, to Iran, Syria and Hezbollah. The misguided and perilous instrumentalization of jihadist organizations is reminiscent of the role assigned to Osama Bin Laden’s Mujahideen in Afghanistan in the 1980s. But this time, the US-backed Saudi, Qatari and Turkish strategies in Syria might prove to be exponentially more disastrous. In the wake of this foolish adventure, religious minorities have nearly disappeared in the so-called “liberated areas” in Syria.

*Talal El Atrache is a Syrian journalist and writer. He worked for many years at Agence France Presse (AFP), and as a correspondent at Radio France Internationale. He has also been a freelance journalist at l’Humanité newspaper, TV5 and BFM TV (French channels). In 2007, he was awarded the Lorenzo Natali Media Prize by the European Commission. He is the co-author, with Richard Labévière, of “Quand la Syrie s’éveillera” (When Syria Awakes), published in 2010 by “Editions Perrin” (Paris).

*Talal El Atrache is a Syrian journalist and writer. He worked for many years at Agence France Presse (AFP), and as a correspondent at Radio France Internationale. He has also been a freelance journalist at l’Humanité newspaper, TV5 and BFM TV (French channels). In 2007, he was awarded the Lorenzo Natali Media Prize by the European Commission. He is the co-author, with Richard Labévière, of “Quand la Syrie s’éveillera” (When Syria Awakes), published in 2010 by “Editions Perrin” (Paris).

Coups, Stability, and Authoritarian Rule

Coups, Stability, and Authoritarian Rule

Upon returning from Egypt, Shishakli was greeted at the airport by the pro-Baath army officer, Adnan al-Malki with demands for political reform. Shishakli had Malki compile a list of everyone involved in the confrontation and threw them in prison.

Upon returning from Egypt, Shishakli was greeted at the airport by the pro-Baath army officer, Adnan al-Malki with demands for political reform. Shishakli had Malki compile a list of everyone involved in the confrontation and threw them in prison. Aside from his coup and military rule, Shishakli was known for preserving Syria’s independence and sovereignty during a period of heightened Western influence in the region. He shunned military aid from the Eisenhower Administration and but also kept Syria from falling into the Soviet Bloc. The Fertile Crescent Project (sometimes referred to as the Baghdad Pact) was the primary driver of the region’s geopolitical trends during his time. The British sphere of influence extended over Iraq and though there was a desire to erase the artificial borders, the potential threat of Western interference led the nationalist forces inside Syria to keep prospects of a union between Damascus and Baghdad at bay.

Aside from his coup and military rule, Shishakli was known for preserving Syria’s independence and sovereignty during a period of heightened Western influence in the region. He shunned military aid from the Eisenhower Administration and but also kept Syria from falling into the Soviet Bloc. The Fertile Crescent Project (sometimes referred to as the Baghdad Pact) was the primary driver of the region’s geopolitical trends during his time. The British sphere of influence extended over Iraq and though there was a desire to erase the artificial borders, the potential threat of Western interference led the nationalist forces inside Syria to keep prospects of a union between Damascus and Baghdad at bay.

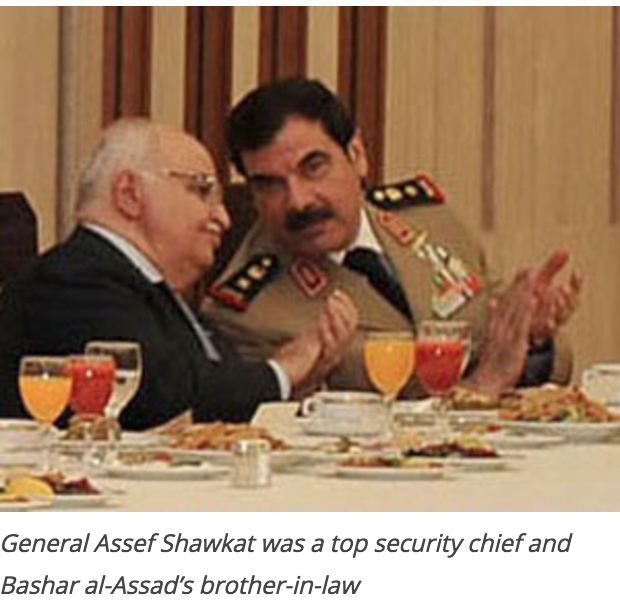

Assassination of Assef Shawkat, the President’s Brother-in-Law, 18 July 2012

Assassination of Assef Shawkat, the President’s Brother-in-Law, 18 July 2012