by Mohammad D for Syria Comment

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the newly minted caliph of the “Islamic State,” chose the first Friday of Ramadan to make his first public appearance—ever. Until now he has worked outside the limelight, and the almost complete absence of his image in public media had generated a sense of mystique around his persona. Now, he has given a public sermon and led prayers at an impressive mosque in Mosul, available in the below video:

Shortly prior, the Islamic State (formerly ISIS, now simply IS), had declared through its spokesperson Abu Muhammad al-’Adnani that it was establishing a khilafa (“caliphate”) in the land it controls in Syrian and Iraqi territory, over which the ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was to be the khalifa (خليفة الله في الأرض, “caliph”). Muslims have now been asked to swear allegiance to this new khilafa.

This comes at the chagrin of many other jihadis who had hoped to beat him to it, who had previously tried and failed, or who had a more “right” approach to doing so. No matter: now that we all know it’s doable, perhaps you’d also like to try your hand at the caliphate game? Here’s a handy manual of the primary words to keep ever upon your tongue as you move through the stages of establishing your own caliphate…

Every jihadi speech contains key words that sum up their purpose and express their objectives. The concepts behind these terms constitute the building blocks for the establishment of khilafa and can help explain the recent rise of ISIS/IS and al-Baghdadi.

The following 6 terms correspond to consecutive stages integral to actualizing the jihadi goal and reveal much about the beliefs that motivate jihadis.

1 – al-Taqwa التقوى

Al-taqwa simply means performing what Allah has ordered of you. It is to obey Allah’s wishes as well as to fear him. “Ittaqi Allah,” a widely used phrase, means fear Allah and obey his wishes. This readiness to follow Allah’s will is an important stage of being that you must reach before embarking on your mission. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in almost all of his speeches, asks the Muslims to be muttaqiin and to yattaqu Allah, both of which mean to do what Allah has set forth in the Qur’an.

In his speech, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi first quoted from the Qur’an’s sura “‘Umran,” verse 102:

يَاأَيُّهَاالَّذِينَآمَنُوااتَّقُوااللَّهَحَقَّتُقَاتِهِوَلَاتَمُوتُنَّإِلَّاوَأَنْتُمْمُسْلِمُونَ

“O you who have believed, fear Allah as He should be feared and do not die except as Muslims [in submission to Him].”

Al-Baghdadi then quotes the sura “al-Ahzab” verses 70-71:

يَاأَيُّهَاالَّذِينَآَمَنُوااتَّقُوااللَّهَوَقُولُواقَوْلًاسَدِيدًايُصْلِحْلَكُمْأَعْمَالَكُمْوَيَغْفِرْلَكُمْذُنُوبَكُمْوَمَنْيُطِعِاللَّهَوَرَسُولَهُفَقَدْفَازَفَوْزًاعَظِيمًا

“O you who have believed, fear Allah and speak words of appropriate justice. He will [then] amend for you your deeds and forgive you your sins. And whoever obeys Allah and His Messenger has certainly attained a great attainment.”

In the second part of his speech, al-Baghdadi told his audience that to yataqqu Allah and begin jihad for his sake is necessary whether they want security, work, or an honorable living.

2 – al-Nafeer النفير

Al-nafeer means, in the jihadi context, mobilization to join the battle. It is the initial step: the switch from life as a civilian citizen of a certain nation-state to the role of a mujahid who obeys a new set of specific rules. The term is drawn from many Qur’anic verses that mention al-nafeer. Anytime a jihadi wants to recruit someone, he invokes al-nafeer and, of course, the related verses in the Qur’an. Also, it is used anytime someone wants to collect money for Jihad.

Al-Nafeer connotes having left everything, making the decision to join the fight, ready to die. The derived verb is nafara نفر(past tense) or yanfuru ينفر(present tense). When someone Yanfur ila Sahat al-Ma’raka (ينفرإلى ساحة المعركة), it means he is ready to die, and is expecting to die with a “guarantee” for a better existence in the afterlife. When a person decides to yanfur (join the fight), jihadists say that he is allowed to disobey his parents and the authorities and is no longer beholden to any laws but those of Islam (and, of course, his sect’s interpretation of Islam). The governments that are fighting the mobilization of their kids for jihad raise this issue frequently, featuring the arguments of religious scholars who oppose the jihadist interpretation.

Of Qur’anic verses mentioning al-nafeer, three are most significant. These verses are loaded with interpretive meaning, and much has been written about them. It is common to hear them referred to in speeches, tweets, sermons, and so forth.

a) إنفِرُواْ خِفَافًا وَثِقَالاً وَجَاهِدُواْ بِأَمْوَالِكُمْ وَأَنفُسِكُمْ فِي سَبِيلِ اللَّهِ ذَلِكُمْ خَيْرٌ لَّكُمْ إِن كُنتُمْ تَعْلَمُونَ

Translation: “Go forth, whether light or heavy, and perform jihad with your wealth and your lives in the cause of Allah. That is better for you, if you only knew” (Qur’an 9:41).

In this verse Allah is ordering the Muslims to conduct al-nafeer, light or heavy. “Light” means you leave your home with nothing. “Heavy” means you leave your country for the land of jihad with money, equipment, etc. The verse then issues the command to join al-jihad with your money and yourself. Here, in common interpretations, those who cannot go make jihad physically are charged to fundraise on behalf of those who can. The belief is that if you prepare a person for jihad (i.e. finance his preparedness for battle), you will be considered as though you have gone to wage jihad yourself.

b) يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُواْ مَا لَكُمْ إِذَا قِيلَ لَكُمُ انفِرُواْ فِي سَبِيلِ اللَّهِ اثَّاقَلْتُمْ إِلَى الأَرْضِ أَرَضِيتُم بِالْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا مِنَ الآخِرَةِ فَمَا مَتَاعُ الْحَيَاةِ الدُّنْيَا فِي الآخِرَةِ إِلاَّ قَلِيلٌ

Translation: “O you who have believed, what is [the matter] with you that, when you are told to go forth [derived imperative of nafeer] in the cause of Allah, you adhere heavily to the earth? Are you satisfied with the life of this world rather than the hereafter? But what is the enjoyment of worldly life compared to the hereafter except a [very] little” (Qur’an 9:38).

This verse is used to admonish those considered lazy, who prefer the contentment of their normal lives over making jihad, neglecting to appreciate the magnitude of the afterlife. (Of course, the afterlife of he who joins jihad is Paradise.)

c) إِلاَّ تَنفِرُواْ يُعَذِّبْكُمْ عَذَابًا أَلِيمًا وَيَسْتَبْدِلْ قَوْمًا غَيْرَكُمْ وَلاَ تَضُرُّوهُ شَيْئًا وَاللَّهُ عَلَى كُلِّ شَيْءٍ قَدِيرٌ

Translation: “If you do not go forth, He will punish you with a painful punishment and will replace you with another people, and you will not harm Him at all. And Allah is over all things competent” (Qur’an 9:39).

In this verse Allah says that if you do not do mobilize (derived verbal form from nafeer) you are going to be tortured severely, and you and your people are going to be substituted by others by Allah, the one able to do anything.

In his speech, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi underscored the importance of joining Jihad, because, according to him, Allah had ordered it so that Islam could be established.

Here is a link to a video in which a Tunisian fighter explains the importance of nafeer and calls people to do nafeer “light” or “heavy:”

3 – al-Ribaat الرباط

For jihadis, al-Ribaat refers to the time spent at the battlefront. Ard al-Ribaat أرض الرباط means the land where the battle occurs or is about to take place, against the enemy. The verb raabata رابط (past tense) or yuraabitu يرابط (present tense) means to spend time in the trenches. The concept is highly revered among Muslims, especially by jihadis. The frontlines are also sometimes referred to as al-thughur الثغور. Keep in mind that all of these words are rarely used in everyday language and have vastly different meanings when used in the modern era.

Al-Ribaat is mentioned in the Qur’an:

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا اصْبِرُوا وَصَابِرُوا وَرَابِطُوا وَاتَّقُوا اللَّهَ لَعَلَّكُمْ تُفْلِحُونَ

Translation: “O you who have believed, persevere and endure and remain stationed and fear Allah that you may be successful” (Qur’an 3:200).

And in the hadith we find emphasis on rewards for those who observe ribaat:

a) رباط يوم في سبيل الله خير من الدنيا وما عليها

Translation: “Observing ribaat for a single day is far better than the world and all that it contains.”

b) رباط يوم وليلة خير من صيام شهر وقيامه، وإن مات فيه جرى عليه عمله الذي كان يعمل وأجري عليه رزقه وأمن من الفتان

Translation: “Observing ribaat in the way of Allah is far better than fasting in the month of Ramadan and all the nighttime worship activities that are associated with that month. And, if one dies while observing ribaat he will go on receiving his reward for his meritorious deeds perpetually and he will be saved from calamities.”

c) رباطيوم في سبيل الله خير من ألف يوم فيما سواه من المنازل

Translation: “Observing a day of ribaat for the sake of Allah is better than a thousand days in any other place.”

d)كل ميت يختم على عمله إلا المرابط في سبيل الله فإنه ينمي له عمله إلى يوم القيامة، ويؤمن من فتنة القبر

In this Hadith we see that whoever does ribaat for the sake of Allah is exempted from the calamities that happen between death and judgment day (special “tortures of the grave” exacted by Allah on the sinful while still in their graves, prior to the judgment).

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi regularly speaks of ribaat, though in his speech he only alluded to it without using the word. In the following video, a missionary of jihad mentions more hadith about al-Ribaat:

4 – al-Thabaat الثبات

Al-thabaat means steadfastness, or to be able to hold your lines in the fight. It also means to stick to your beliefs, and in this case, your decision to fight. It is the ability to stay put in the face of adversity in the “arenas of jihad.” In their speeches, many jihadis call for the strength to stay true to the goal. Many historical references are made in conjunction with this term, most importantly to events from the days of the Prophet Mohammad, such as the battle of Uhud. Frequent references to Qur’anic verses mentioning the term are made.

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا إِذَا لَقِيتُمْ فِئَةً فَاثْبُتُوا وَاذْكُرُوا اللَّهَ كَثِيرًا لَعَلَّكُمْ تُفْلِحُونَ

Translation: “O you who have believed, when you encounter a company [from the enemy forces], stand firm and remember Allah much that you may be successful” (Qur’an 8:45).

This above verse is used by jihadis on a regular basis. It asks the believers to hold their position and pray to Allah when faced with adversaries in battle. It is therefore very important to every jihadi to read the Qur’an and hadith and to mention Allah whenever he is in battle. The word “Allah” and the adjectives normally attached to it are abundant in jihadi rhetoric, sprinkled within almost every sentence any jihadi utters.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdai mentioned al-thabaat in the second part of his speech. He beseeched Allah to “yuthabet” (hold firm) the feet of the mujahideen. The Qur’anic references for al-Baghdadi are these verses:

ولمابرزوالجالوتوجنودهقالواربناأفرغعليناصبراوثبتأقدامناوانصرناعلىالقومالكافرين

Translation: “And when they went forth to [face] Goliath and his soldiers, they said, ‘Our Lord, pour upon us patience and plant firmly our feet and give us victory over the disbelieving people’” (Qur’an 2:250)

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا إِنْ تَنْصُرُوا اللَّهَ يَنْصُرْكُمْ وَيُثَبِّتْ أَقْدَامَكُمْ

Translation: “O you who have believed, if you support Allah, He will support you and plant firmly your feet” (Qur’an 47:7).

Al-thabaat also has a lot to do with courage. It is very common to hear every jihadi and suicide bomber include the word thabaat in their speeches—even Chechens and other non-Arabic-speakers use this word prolifically. A very common phrase is to ask Allah for al-thabaat: “…نسأل من الله الثبات”

5 – al-Tamkeen التمكين

Al-tamkeen means simply to be able to control what you have taken and establish yourself within it. The Qur’an provides the basis for the concept of tamkeen as something done over a piece of land. At this stage the group must create the infrastructure of a state. Islamic scholars have, of course, written volumes about it, but the basic idea is conveyed by the following Qur’anic verse:

وَنُرِيدُ أَنْ نَمُنَّ عَلَى الَّذِينَ اسْتُضْعِفُوا فِي الْأَرْضِ وَنَجْعَلَهُمْ أَئِمَّةً وَنَجْعَلَهُمُ الْوَارِثِينَ وَنُمَكِّنَ لَهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ وَنُرِيَ فِرْعَوْنَ وَهَامَانَ وَجُنُودَهُمَا مِنْهُمْ مَا كَانُوا يَحْذَرُونَ

Translation: “And We wanted to confer favor upon those who were oppressed in the land and make them leaders and make them inheritors, and establish them in the land” (Qur’an 28:5-6).

الَّذِينَ إِنْ مَكَّنَّاهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ أَقَامُوا الصَّلَاةَ وَآتَوُا الزَّكَاةَ وَأَمَرُوا بِالْمَعْرُوفِ وَنَهَوْا عَنِ الْمُنْكَرِ ۗ وَلِلَّهِ عَاقِبَةُ الْأُمُور

Translation: “Those who, if We give them authority in the land, establish prayer and give zakah and enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong. And to Allah belongs the outcome of [all] matters” (Qur’an 22:41).

وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا مِنْكُمْ وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ لَيَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ كَمَا اسْتَخْلَفَ الَّذِينَ مِنْ قَبْلِهِمْ وَلَيُمَكِّنَنَّ لَهُمْ دِينَهُمُ الَّذِي ارْتَضَىٰ لَهُمْ وَلَيُبَدِّلَنَّهُمْ مِنْ بَعْدِ خَوْفِهِمْ أَمْنًا ۚ يَعْبُدُونَنِي لَا يُشْرِكُونَ بِي شَيْئًا ۚ وَمَنْ كَفَرَ بَعْدَ ذَٰلِكَ فَأُولَٰئِكَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُونَ

وَأَقِيمُوا الصَّلَاةَ وَآتُوا الزَّكَاةَ وَأَطِيعُوا الرَّسُولَ لَعَلَّكُمْ تُرْحَمُونَ

Translation: “Allah has promised those who have believed among you and done righteous deeds that He will surely grant them succession [to authority] upon the earth just as He granted it to those before them and that He will surely establish for them [therein] their religion which He has preferred for them and that He will surely substitute for them, after their fear, security, [for] they worship Me, not associating anything with Me. But whoever disbelieves after that – then those are the defiantly disobedient. And establish prayer and give zakah and obey the Messenger – that you may receive mercy” (Qur’an 24:55-56).

In his speech, al-Baghdadi stressed this concept. He said that having the might to do tamkeen is part of observing Islam correctly (being able to force others to do what you believe is right), and quoted this verse:

لَقَدْ أَرْسَلْنَا رُسُلَنَا بِالْبَيِّنَاتِ وَأَنْزَلْنَا مَعَهُمُ الْكِتَابَ وَالْمِيزَانَ لِيَقُومَ النَّاسُ بِالْقِسْطِ ۖ وَأَنْزَلْنَا الْحَدِيدَ فِيهِ بَأْسٌ شَدِيدٌ وَمَنَافِعُ لِلنَّاسِ وَلِيَعْلَمَ اللَّهُ مَنْ يَنْصُرُهُ وَرُسُلَهُ بِالْغَيْبِ ۚ إِنَّ اللَّهَ قَوِيٌّ عَزِيزٌ

“We have already sent Our messengers with clear evidences and sent down with them the Scripture and the balance that the people may maintain [their affairs] in justice. And We sent down iron, wherein is great military might and benefits for the people, and so that Allah may make evident those who support Him and His messengers unseen. Indeed, Allah is Powerful and Exalted in Might” (Qur’an 57:25).

After using this Qur’anic text, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi shouted a slogan of ISIS (the “foundation of religion” phrase from Ibn Taymiyah which is very important for jihadis), which is as follows: “The foundation of the religion is a book that leads and a sword that supports it” (قوام الدين كتاب يهدي وسيف ينصر).

The concept of tamkeen can explain why jihadis make the call for prayer every time they overrun a post. In their creed, the power to raise your voice in the call to prayer is a sign of tamkeen—that you have control over the place. The verbal form of this word is also used when ISIS soldiers are leading prisoners of war or after they behead someone, in such phrases as: “We thank Allah who made us control their necks” (نشكر الله الذي مكننا من أعناقهم).

6 – al-Istikhlaf الإستخلاف

Al-istikhlaf is derived from the same root as the word khilafa (caliphate). This is when you, as a jihadi, get to kick it into the net: now that you’ve followed the rules, carried out Allah’s will, fought for the land, implemented control after being granted the land by Allah, it is now time for the final step—the establishment of a khilafa, i.e. a state that follows shari’at Allah, the laws of Allah. Just remember that for your caliphate to be a legitimate one—not just a crazed delusion proclaimed by some fanatical wanabees—you must follow all the right steps, as outlined here, leading up to this one.

Al-Baghdadi spoke extensively on the concept of istikhlaaf in his speech, saying that after his group was able to exercise control it became their Islamic duty to declare a khilafa—the duty that Muslims had “lost for centuries.” He stressed that “Muslims should always try to establish it [khilafa].”

Al-istikhlaf is based on several Qur’anic verses and hadiths:

قَالَ عَسَى رَبُّكُمْ أَنْ يُهْلِكَ عَدُوَّكُمْ وَيَسْتَخْلِفَكُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ

Translation: “He said ‘Perhaps your Lord will destroy your enemy and grant you succession in the land and see how you will do” (Qur’an 7:129).

وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا مِنكُمْ وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ لَيَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُم فِي الْأَرْضِ كَمَا اسْتَخْلَفَ الَّذِينَ مِن قَبْلِهِم

Translation: “Allah has promised those who have believed among you and done righteous deeds that He will surely grant them succession [to authority] upon the earth just as He granted it to those before them…” (Qur’an 24:55).

The Qur’an mentions in many verses that the believers will inherit the earth. It also states that Allah owns the land and that he will give it to his favorite followers.

Conclusion – Ready to Establish Your Own Caliphate, Baghdadi Style

If you’ve taken notes on the necessary stages of the jihadi project, you’re better prepared to follow al-Baghdadi’s example and pursue the establishment of your own caliphate (provided you purify your heart and all that). If you’re lucky, the loyal men you’ve surrounded yourself with (who don’t dare express dissent since they know death will be the penalty) will ‘elect’ you as the caliph!

In his first-ever public appearance, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi wanted to demonstrate his control and prove that the time to remain hidden has passed. As khalifa, he can now choose his whereabouts and act as a public figure. Far from featuring Ramadan as the spiritual journey it is understood to be by most Muslims, al-Baghdadi turned it into a jihad-fest. In the first sermon of Ramadan, he called Muslims to join the jihad and build khilafa. He came dressed in black and walked with a limp, conveying that he had been wounded in the jihad.

Al-Baghdadi performed the duties of a khalifa: giving a sermon and leading the people in prayer. He brandished his linguistic skills and some admirers praised him for having improvised his speech. But don’t let this intimidate you regarding your own aspirations: if you really follow the speech of jihadis, you’ll find that they repeat a very finite number of limited concepts, encapsulated within the same few-dozen cookie-cutter sentences.

The post The Six Words You Need to Know to Be a Successful Jihadi and Establish Your Own Caliphate appeared first on Syria Comment.

by Matthew Barber

by Matthew Barber

What Motivates European Youth to Join ISIS?

What Motivates European Youth to Join ISIS?

Loretta Bass’ most recent book is, African Immigrant Families in Another France (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2014). Loretta can be contacted at: lbass@ou.edu and is presently on sabbatical in Frankfurt, Germany.

Loretta Bass’ most recent book is, African Immigrant Families in Another France (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2014). Loretta can be contacted at: lbass@ou.edu and is presently on sabbatical in Frankfurt, Germany.

2014 Roundup and 2015 Predictions

2014 Roundup and 2015 Predictions

Jihadis and extremists prevailed

Jihadis and extremists prevailed The creation of new states was the rage in 2014.

The creation of new states was the rage in 2014. I have spoken at some length about the

I have spoken at some length about the  Syria is locked into perpetual war

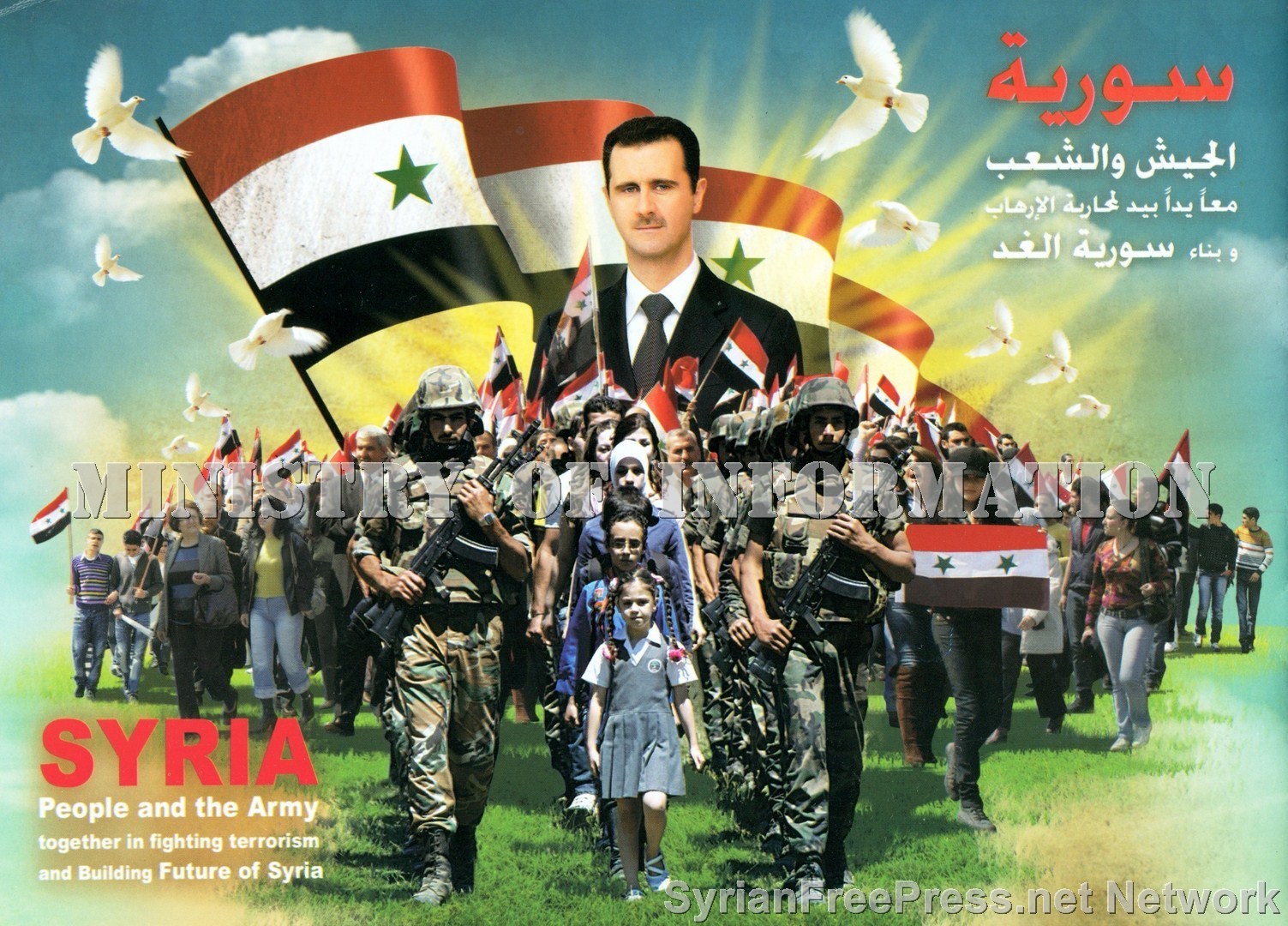

Syria is locked into perpetual war Is the Syrian Army a Bulwark against Extremism?

Is the Syrian Army a Bulwark against Extremism? 2014 was the year of ISIS

2014 was the year of ISIS By viewing the footage, IS does a kind of violence to me—or perhaps I am doing violence to myself by choosing to watch. There seems to be something problematic about becoming consumers of this horrific product that IS pushes. Does that extend to the political analyst? The intelligence analyst? Who legitimately needs to consume this product and who should not view it?

By viewing the footage, IS does a kind of violence to me—or perhaps I am doing violence to myself by choosing to watch. There seems to be something problematic about becoming consumers of this horrific product that IS pushes. Does that extend to the political analyst? The intelligence analyst? Who legitimately needs to consume this product and who should not view it?